… what is it good for?

What I was thinking about:

Some of you will know my thoughts about war. I’ve been there so I feel my opinion is valid and qualified. For a very long time, I wasted my angst on what it did to me, when the real issue lies buried deep within the genetic code of the human being. Society’s “norms”, there for eons, directly opposed my reintroduction to that society. They hated me for going, I hated them for sending me.

Yet we were stuck with each other. How’s that for quandary? Nothing I could envision or do would make any difference in the outcome. Believe me. I tried. There will be more war. And people like me would fight them, all in the name of “Peace”. Today, we must seek understanding and coexistence.

Several weeks ago, I asked Grok to research the term “peace through strength” on the global stage. You wouldn’t believe how much relevant content it found. Had I let it continue searching, I think it still would be generating data. It was on page 100 when I canceled the request at the cost of 100 points. 😒

I refined the query to list instances in history where harmony was sought through war. I also gave it a word count limit and told it to find times when war was specifically justified by the instigator in the guise of seeking peace.

There was still an encyclopedic volume of instances. From Chinese clan wars in the times of Confucius and Sun Tzu, to the Roman’s Pax Romana, the Crusades, through the War to end all Wars, peace has been used time and again as the reason to go to war. Today we have Nation Building, or Invasions to collect and prevent the use of WMDs that may or may not exist.

The result of that research was much more manageable and far less daunting. I then dug deeper to add depth and more historical content to what I thought were salient points. I love doing this, but I get bored if any subject takes too long. That’s why this took about 4 weeks to complete. 🤭🫣🤫I have a secret weapon now though. I use two very large monitors, so I can have the data on one screen and be blogging it on the other.

Here’s what I gleaned from 47 pages of data.

A Paradoxical Pursuit: The Irony of Seeking Peace Through War

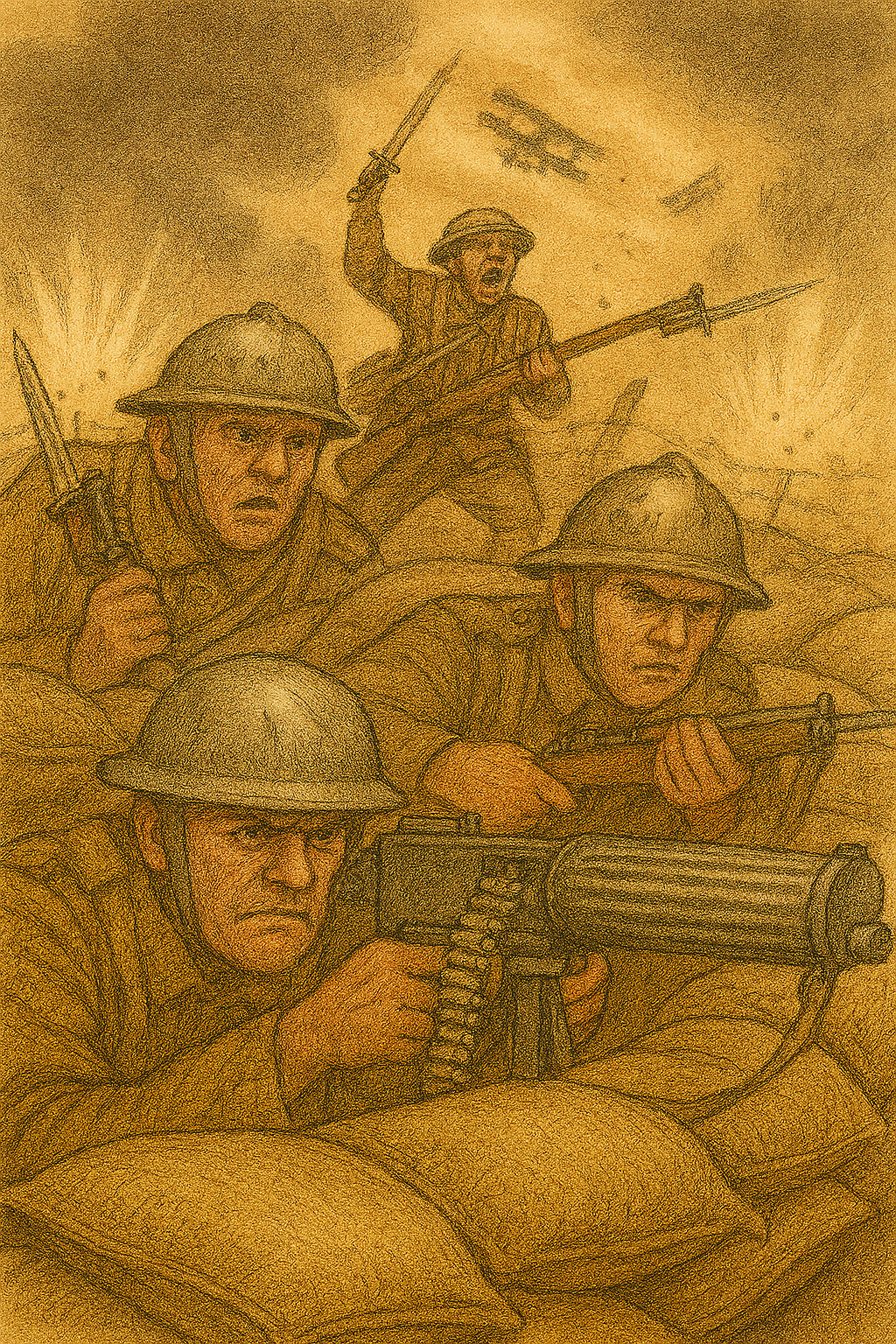

The concept of seeking peace through war is one of humanity’s most enduring and tragic ironies. It embodies a fundamental contradiction: the use of violence, destruction, and death as a means to achieve harmony, stability, and tranquility. This paradox has been woven into the fabric of human history, philosophy, and politics, often justified under banners of “just war,” “defensive aggression,” or “peacekeeping missions.”

Yet, time and again, the pursuit of peace via warfare reveals itself as a self-defeating cycle, where the tools of conflict undermine the very goal they purport to serve. In this essay, we will explore this irony in depth, drawing on historical examples, philosophical insights, psychological underpinnings, and modern manifestations. Ultimately, I will make an argument—albeit a provocative and counterintuitive one—that perhaps we should abandon the quest for peace altogether, as its relentless pursuit only perpetuates the wars we claim to abhor.

ABSENCE vs PRESENCE

To understand the irony, we must first define peace and war in their stark opposition. Peace is typically envisioned as a state of absence: absence of tension, violence, fear, and oppression. It is a positive ideal, encompassing justice, cooperation, and mutual prosperity. War, conversely, is the epitome of presence: the active deployment of force, the imposition of will through bloodshed, and the disruption of societal norms.

The irony arises when war is framed as a necessary precursor to resolution—a “war to end all wars,” as Woodrow Wilson famously described World War I. This phrase, coined in the aftermath of the Great War, encapsulates the delusion. World War I, with its unprecedented scale of death (over 16 million lives lost), was meant to usher in an era of lasting stability through the League of Nations. Instead, it sowed the seeds for World War II, which claimed even more lives (estimated at 70-85 million).

The treaties, like the Treaty of Versailles, imposed punitive measures on Germany, fostering resentment and economic despair that fueled Hitler’s rise. Here, the irony is palpable: the war intended to secure stability created conditions ripe for greater conflict.

Precedents

Historical precedents abound. Consider the Roman Empire’s Pax Romana, a period of relative tranquility lasting about 200 years from 27 BC to 180 AD. This “peace” was achieved through relentless military conquests, subjugation of peoples, and the maintenance of a vast standing army. The Romans justified their wars as bringing civilization and order to barbarians, yet this tranquility was enforced at the point of a sword.

As Tacitus wryly noted in Agricola, the Romans “make a desert and call it peace.” The irony lies in the fact that true harmony cannot be imposed; it must emerge organically. The empire’s eventual collapse under the weight of its own militarism underscores how war-based stability is inherently unstable.

Audio version of Agricola by Tacitus. this is endlessly fascinating if you can get past the idioms of the day.

Moving to the medieval era, the Crusades (1095-1291) were launched under the guise of holy wars to reclaim Jerusalem and secure religious peace. Pope Urban II rallied Christians with promises of salvation and eternal peace in heaven, while framing the campaigns as defensive against Muslim aggression.

The result? Centuries of bloodshed, cultural devastation, and deepened divisions between East and West. The irony is that these campaigns, meant to unite Christendom in equilibrium, fragmented it further, leading to internal schisms like the sack of Constantinople by Crusaders in 1204. Peace through holy war proved not only illusory but counterproductive, entrenching hatreds that persist in modern religious conflicts.

In the modern age, the irony manifests in colonial and imperial ventures. European powers in the 19th century justified colonialism as a “civilizing mission” to bring stability and progress to “savage” lands. Britain’s Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1860) against China were ostensibly about free trade and ending isolationism, but they were wars of aggression to force opium sales, leading to addiction epidemics and social upheaval.

The “peace” that followed was one of unequal treaties and exploitation, breeding revolutions like the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), which killed tens of millions. Similarly, the U.S. doctrine of Manifest Destiny framed westward expansion and wars against Native Americans as bringing resolution through settlement and democracy. Yet, this resulted in genocide, forced relocation like the Trail of Tears, and ongoing inequalities. The irony: wars for stability often mask greed and power grabs, leaving legacies of unrest.

What of the societal woes brought on by the onslaught of conflict? What occurred in the USA in the 1960s and 70s was catastrophic in so many ways. For the first time, we were not united in war. We were divided by it, and it nearly wiped us out. There are still repercussions of that fallout present today. Do we yet trust our government and leaders? The answer, I’m afraid, is a resounding no. One side of our coin is adamantly opposed to the other, always and relentlessly. Personally, I see no end, just more conflict, more of this ‘Peace through War’ mentality.

Philosophy

Philosophically, thinkers have grappled with this paradox. Immanuel Kant, in his essay Perpetual Peace (1795), argued for a federation of republics to achieve lasting peace, but acknowledged that wars might be necessary to dismantle tyrannies. However, he warned against the “moral evil” of using war as a tool. Karl Marx viewed wars as extensions of class struggles, where bourgeois interests cloak economic exploitation in peaceful rhetoric.

The irony, for Marx, is that capitalist wars promise peace through victory but only redistribute power among elites, perpetuating worker oppression. Friedrich Nietzsche took a more cynical view, suggesting in Thus Spoke Zarathustra that peace is a decadent illusion, and war is the true driver of human greatness. Yet even Nietzsche recognized the irony: societies that glorify war for peace’s sake often descend into barbarism.

Psychology

Psychologically, the irony stems from cognitive dissonances in human behavior. Prospect theory, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, explains how people are loss-averse, willing to risk war to avoid perceived threats to peace. Leaders frame wars as preventive—e.g., the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 to eliminate weapons of mass destruction and promote democracy. The irony: no WMDs were found, and the war destabilized the region, birthing ISIS and endless insurgencies. Groupthink, as Irving Janis described, amplifies this, where decision-makers in echo chambers rationalize war as the path to peace, ignoring evidence to the contrary.

Geopolitics

In contemporary geopolitics, the irony persists. NATO’s interventions, such as in Libya (2011), were billed as humanitarian wars to prevent atrocities and foster peace. The result? A failed state, arms proliferation, and regional instability. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (2022-present) is justified by Putin as a “special military operation” to denazify and secure peace for Russian speakers.

Yet, it has caused massive civilian casualties and global economic shocks. The United Nations, founded to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war,” oversees peacekeeping missions that often involve armed forces, blurring the line between war and peace. Drone strikes in the War on Terror promise precise, “clean” warfare to achieve security, but they create cycles of revenge and radicalization.

Economy

Economically, the military-industrial complex, as Dwight D. Eisenhower warned in 1961, profits from this irony. Defense contractors lobby for wars under the pretext of maintaining peace through strength. The U.S. spends over $800 billion annually on defense, more than the next ten countries combined, ostensibly for global peace. Yet, this arms race escalates tensions, as seen in the Cold War’s proxy conflicts. The irony: resources poured into war preparation could fund education, healthcare, and diplomacy—true builders of peace. This struck home with me as here is an absolute war hero, barking at the financiers of war.

Culturally, media and propaganda perpetuate the paradox. Films like Saving Private Ryan glorify sacrificial war for ultimate peace, while ignoring long-term traumas. Video games simulate wars as heroic quests for order. This desensitizes societies, making war seem a viable route to peace.

Why not War

Now, turning to the provocative argument: perhaps we should stop seeking resolution altogether. This may sound nihilistic but hear me out. The relentless pursuit of harmony has become a dangerous obsession, one that justifies endless wars in its name. By idealizing harmony as an attainable utopia, we set ourselves up for failure and hypocrisy. Every failed attempt—be it Versailles, Yalta, or Camp David—breeds cynicism and more violence. If peace is the absence of war, but seeking it provokes war, then abandoning the quest might break the cycle. Don’t you think?

Consider the benefits of embracing conflict as inherent to human nature. Evolutionary biology suggests humans are wired for competition; suppressing it under “peace” leads to repressed aggression that erupt catastrophically. By stopping the search for peace, we could focus on managing conflicts transparently—through limited skirmishes, economic rivalries, or even ritualized duels—without the delusion of eradication. History shows that eras without grand peace narratives, like the Warring States period in China (475-221 BCE), fostered innovations in philosophy (Confucius, Sun Tzu) and technology, leading to unification under Qing without pretense.

Philosophically, abandoning peace aligns with existentialism. Jean-Paul Sartre argued that humans are condemned to freedom, including the freedom to conflict. Seeking peace imposes inauthentic harmony, denying our essence. Nietzsche’s “will to power” posits that striving for dominance, not peace, drives progress. In a world without peace as a goal, we might achieve de facto stability through mutual deterrence, as in the Cold War’s MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) doctrine, which prevented nuclear war not through peace efforts but through fear of annihilation.

Practically Speaking

Practically, stopping the pursuit could redirect resources. Imagine trillions saved from peacekeeping budgets invested in space exploration or AI development—arenas, where competition spurs advancement without mass death. Socially, it could foster resilience; societies that accept strife build stronger individuals, less prone to fragility.

Ahem!

Of course, this argument is tongue-in-cheek, a mirror to the irony itself. True abandonment of harmony is impossible, as it’s ingrained in our aspirations. But by highlighting the absurdity, we underscore how the irony persists: even arguing against peace is a bid for a different kind of harmony. Ultimately, the path forward lies not in war for resolution, nor in forsaking harmony, but in humble diplomacy, empathy, and recognition of our shared flaws.

I don’t know that ‘humble’ is still a possibility today. It seems that being contrite only emboldens the greedy. We’ve seen countless examples of bad actors taking advantage of a situation. Ukraine is the perfect modern-day example of the futility of seeking peace while both sides are slinging accusations, are armed to the teeth and not willing to budge.

Peace. The most elusive of all mankind’s goals.

An earlier discussion about the effects of war.

Popi sends…